| Wenceslao Rosell U. |

The Peruvian Paso Horse, his gait and training

W. Rosell, july 1945

Some people claim to possess secrets regarding the training of the national horse, and since they rarely share them, these valuable insights are sadly lost to future generations. These secrets are connected to what the locals refer to as the “training of the national horse.” As far as I know, no written documentation exists on this subject, which has also prompted me to write this booklet, hoping to convince my readers that training a horse is neither a trivial nor an arbitrary task. It cannot be done haphazardly or on a whim without understanding the reasons behind the movements we ask of the animal or teach it. Often, the process is carried out through mere imitation and nothing more, lacking the necessary care and skill—care and skill that only come from the innate vocation of a true rider or horseman, who, needless to say, are very rare.

The science of understanding and guiding a horse is inherently complex. It is well known that there are two methods to reach any scientific truth: observation and experience.

Well, based on my own experience and observations, I believe it should be considered an axiom of horse training and riding that, to properly educate this noble companion of man, every enthusiast must remember that better results and more positive outcomes are achieved by using constant attention and affection rather than misguided rigor.

This principle stems from the fact that, in the horse’s subtle instinct, the factor of memory prevails over intelligence. I have often observed that a horse always remembers a timely caress but does not easily forget undue punishment.

CHAPTER I

Constitution and Characteristics

THE HEAD

The head is lean, somewhat small, with a straight or slightly convex profile (the convex or “ram” profile is also characteristic). The muzzle is short, the jaw strong, pronounced, and rounded. The head has a broad forehead and a narrow muzzle, giving it a “coffin-shaped” appearance. The ears are small, soft, mobile, flexible, and slightly curled. The forehead is broad and slightly arched, with round, calm eyes set wide apart and positioned low on the forehead. The nostrils are elongated, with a pronounced outer wing. The mouth is small, with thin lips and a tucked-in chin. The branches of the jaw are widely separated.

THE NECK

The neck is short, thick, and convex, muscular yet flexible, with an abundant mane of silky hair.

THE BACK

The withers are low and fleshy. The back is slightly saddled, broad, and moderately short, shaping a wide chest. The loin is short, wide, and muscular. The croup is slightly sloped, broad, and sometimes split. The chest is wide and prominent, with well-separated shoulders corresponding to a deep thorax and well-arched ribs. The back is slightly sloped, with the arm and forearm muscular and firm. The long, strongly arched ribs provide ample thoracic capacity. The flank and abdomen are short and rounded. The tail is thick, wavy, and set moderately low, lying close to the thighs, which are elongated and extend nearly to the hocks, which are angled and dry.

The knees are broad and strong, proportionate to the limbs. The cannon bones are short, with straight and prominent tendons. The fetlocks are rounded and dry, while the pasterns are fine and slightly sloped, giving a sense of flexibility. The hooves are short and hard. The skin is soft and thin, covered with fine, shiny hair. Solid coat colors are the most sought after, particularly grays and chestnuts.

CHAPTER II

Description of Its Gait

To clarify this subject, as some enthusiasts have argued otherwise, I maintain that its forward movement is lateral while its support is diagonal, resulting in an intermediate between two extremes: the trot, where the movement is diagonal and simultaneous (lifting the right hind leg and left foreleg from the ground), and the “huachano” gait, where the movement is lateral (right hind leg and right foreleg moving simultaneously, like in the trot). I will now describe the “motor horse,” which is composed of:

1. A Regulator

The head serves as the regulator of speed during movement: the higher the head, the lower the speed.

This regulator has a neutral point that prevents the horse from leaning on the bit (becoming heavy in the mouth) or from “uncovering” (raising the nose into the wind).

Every horse has this neutral point, though it varies depending on the shape and length of the neck. It is discovered gradually through proper handling until the horse understands it. The rider finds this point by lifting one of the reins of the bit: any rein will do if moving in a straight line, and the outside rein if moving in a circle, to lift the head.

Once this position is achieved, the rider applies pressure with the stirrup, heel, or spur on the girth to lower the head (the spur applied to the girth is the most effective lowering aid, far superior to other devices like martingales). Whether using the stirrup, heel, or spur depends on the horse’s energy and sensitivity.

In this interplay of raising and lowering the head, when the horse stops making the aforementioned mistake, you have found the neutral point, which must be maintained—this is the proper contact with the mouth.

2. A Motor (Engine)

The motor is formed by the hindquarters, starting from the loins, and is controlled by the legs and spurs, with the bit used very gently. The legs work in combination with the stirrups, heels, or spur on the girth to halt the movement, meaning the hind legs move under the body mass.

If these aids are applied softly and intermittently, the horse cannot move forward—it is braked. This is the principle of collection.

Once in this position, the rider switches the spur or heel behind the girth to accelerate forward movement, ensuring the horse does not take a step backward with either hind leg. If it does, the rider should return it to the collected position and then immediately accelerate forward. This is the principle of impulsion.

3. A Shock Absorber

The shock absorber is the forehand, which only comes into play through the combination of the motor (hindquarters) and the regulator (head).

4. A Key

The “key” is the loin, which allows the horse to brake through its contraction and, through its elasticity or freedom of movement, enables the horse to break into motion.

The “steam” or power of this motor comes from the proper use of braking and breaking into motion with precise cadence of the hands. Continuous use of braking and starting increases the horse’s intensity; the greater the intensity, the stronger the motor (another principle of impulsion).

As we can see, the importance of the motor-horse lies in its two extremes: the head and the hindquarters, with the loins acting as a hinge, greatly aiding or facilitating their function.

Once this principle or comparison is accepted, it becomes clear that the forward movement of the gaited horse is lateral. The movement begins with one of its hind legs—the motor—which is followed by the foreleg on the same side. With this in mind, I will now describe its gait or movement.

The left hind leg moves and comes under the body mass, prompting the movement of the left foreleg. As the left hind leg touches the ground, the left foreleg is still in the air, placing the horse in a diagonal support—left hind leg and right foreleg. The right hind leg, left behind, then lifts so that as the left foreleg touches the ground, it can come under the body, stepping on or over the track left by the left foreleg. This happens alternately on both sides.

With this explanation, I will now define each type of movement, commonly referred to as “piso” (stride or step).

First: The “SOBREANDANDO” (Over-Walking).

This gait is characterized by a more unified sound in its execution and hoofbeats, due to the immediate lifting of the foreleg in relation to the placement of the hind leg under the body mass. It is the gait with the highest level of activity and one of the fastest in terms of forward movement (being the easiest to artificially induce by a trainer).

Second: The “PASO LLANO” (Flat Walk).

There are several types of “Paso Llano,” including:

a) “PICADO” (Pecking)

This is the most difficult to distinguish from the “sobreandando,” as it differs only by a slight delay in the movement of the hind leg relative to the foreleg, creating a distinct tapping sound, making the hoofbeat sharper. While walking, these horses lift their backs, resulting in a stronger impact when their hooves touch the ground.

The back lift and the force of the hoof strike are highly noticeable to both the observer and the rider.

Horses that master this gait are very rare and exhibit the following characteristics:

- Arrogant demeanor

- Dynamic chest movement

- High head carriage

- Great enthusiasm

b) “EL GATEADO” (Cat-Like Walk)

This gait is similar in execution to the previous one but differs in its calmness and poise, as well as its smoothness and significant forward movement. It is the most consistent gait, maintaining its rhythm whether walking slowly or at a faster pace.

The colts “Limeñito” owned by the Aspillaga Anderson family, and “Príncipe”owned by Federico La Torre Ugarte (father and son), in their gait, could be compared to a swimmer battling against the current. In the formidable movement of these horses, beyond seeing them grip the ground with their powerful strides, it gave the illusion that the earth itself was sliding beneath their hooves.

c) “EL BOBO” (The Clumsy)

This gait is similar in execution to the previous ones but differs in its slower pace, strong hoofbeats, and the horse’s posture, characterized by a lower head carriage with slight oscillating movements.

d) “EL GOLPEADO” (The Striking)

This gait is marked by a delay in the coordination of the fore and hind legs, making the horse prone to diagonalization (trot). It is also characterized by a significant lift of the shoulders and a heavier impact when the hooves strike the ground compared to the previous gaits.

I refrain from describing the so-called Aguilillo because I do not consider it among the valued “gaits,” as it is merely a short, quick step without any elegance.

Chapter III

Balance

Before delving into the subject of enfrenadura (bridling), I must state in advance that what is traditionally taught about it is very limited, reduced to circles, turns, half-turns, sentada (backing), and cejada (reining back). This can be learned in a short time, which raises the question of why horse trainers (chalanes) usually take a year to deliver a fully trained horse according to our customs. The answer lies in what we call asegurado—the horse must maintain a steady and defined gait, with a soft mouth that does not lean on the bit. Achieving this balance requires time, and that is what justifies the delay.

Where did the balance in the enfrenadura of our horses originate? Was it from Spanish or Portuguese horsemanship?

I cannot definitively say which of the two influenced the Viceroyalty. However, my belief is that it was the Portuguese tradition. The Spanish school, as we saw in the renowned rejoneador and equestrian master “El Cañero,” focuses on balance in the hands, with a somewhat low neck, and thus, low shoulders. He controlled the horse’s head using long-shanked bits, but in this posture, the hindquarters—the engine—were not consistently beneath the body mass, as the low neck prevented proper elevation, causing the horse to lean forward.

In contrast, the elegant Portuguese equestrian Don Ruy da Câmara, highly acclaimed in Spain and Portugal and praised in Spanish newspapers as “the horseman of all ages,” controlled the horse’s head with spurs close to the body, without relying on the bit. He commanded with precision and maintained the hindquarters under the body mass, with the neck held high to the fullest extent of the horse’s ability. In essence, he kept the horse fully balanced between his hands and legs, achieving what is known as alta escuela (high school), with perfect and constant balance. Since this posture closely resembles the balance of our horses, I believe it is from this tradition that our enfrenadura originated.

Having mentioned alta escuela, I will now describe it succinctly, avoiding rhetorical embellishments. While the art of horsemanship, particularly this aspect, is a beautiful subject for those gifted in prose, and with technical knowledge, it can provide readers with delightful entertainment, transporting them on wings of imagination to the heights of the ideal.

Equitation, as an art, is considered the most challenging of all arts because, unlike the painter, musician, or sculptor, it is performed with a living being—the horse—possessing both intelligence and will.

As I have already stated, I find it necessary to provide this description because I believe that the posture of our well-bridled horse aligns with that of alta escuela. This posture or balance is easier to achieve in the Peruvian horse due to its noble temperament, strong character, responsiveness to the bit, and sensitivity to leg aids, spurs, or cues. This facilitates equestrian tact because the Peruvian horse’s movements are smooth and free of the diagonal bounce characteristic of the trot.

To describe this alta escuela balance, I will say that, whether at a walk, gait, canter, or any other pace, the horse must carry its head at the height allowed by its neck, enabling the rider to find the neutral point in the bit’s contact with the mouth, (Lamina 2).

The horse’s forehead should remain vertical or slightly forward the kidneys contracted in proportion to the height of the head, naturally positioned behind the center of gravity, and through these movements, the back is free and arched upwards, with expression in its muscles, eyes, ears, and the engagement of the hindquarters. This shows great character demonstrated by the desire to move or by a natural or induced impulsion, which is essential to achieve this posture or balance.

All of this must harmonize with the rider’s seat, complemented by that impulsion or desire to move, ensuring that the horse’s state of energy is not a form of resistance. In this state, the horse submits not only to the physical aids but also seems to respond almost to the transmission of thought, surrendering the lower jaw to the contact of the rein. Our horses express this not by chewing on the bit with a dry mouth, opening and closing their mouths, or moving both jaws continuously and disorderly, but rather by lifting and lowering the port of the bit in search of support, with a moist mouth.

In this state, when the horse tastes the bit, it only moves the lower jaw. As can be understood, all resistance to the bit operated by the rider’s hand disappears, whether the horse is moving forward or when asked to perform a movement, sit back, or rein back. The horse becomes, as it is said, at the rider’s will, fully controlled and balanced between the hands and legs.

This state, referred to as enfrenadura (correct bitting), should not be confused with a horse that is merely moving rhythmically without sufficient engagement. Such horses may lack the will to move forward more energetically or have been taught a rhythmic gait with frequent halts without proper collection, often carrying the head in front of the vertical. These horses are described as well set(bien entablados) but not well bitted (bien enfrenados).

Throughout this process, the reins should not be held short but rather loose to allow impulsion to flow freely, while always ready to establish contact. This permits the neck to remain free, giving the rider a clear sensation of the horse growing under them, as if the horse were lifting through the forehand. It is at this moment, and only then, that the rider can showcase their control by replacing the reins with fragile strips of paper.

This balance, as described, represents the perfectly bitted horse, whose rules of movement I will explain later.

CHAPTER IV

Training

If the gait or movement of our horse is unique in the world, so too is its bridlework, which is distinct from both local and traditional riding schools in its three stages: ordinary riding, value-enhancing riding, and haute école. It closely resembles the latter, as seen in its balance, though it deviates in some profound ways that I believe are due to the lack of written documentation on the subject. Over time, this has led to a degeneration in the understanding of aids, which were originally diagonal (haute école) and have shifted to lateral (ordinary riding). This shift has led to a devaluation of the loose rein bridle (direct rein), placing greater importance on the opposite rein.

If the loose rein did not suffer from the critical error of assisting with the inner stirrup—that is, using the stirrup on the same side as the rein being activated to turn or bend the horse’s neck—and then releasing when the movement is completed, it would instead perform the value-enhancing school. This school is characterized by using the outer stirrup, heel, or spur to fold the horse inward, directing its hindquarters inward and thus preventing the excessive outward inclination of the back and the complete disengagement of the engine, which ends up functioning like a motor running out of sync.

If the aforementioned aids were applied—that is, the inner rein and the outer leg—they would become diagonalized, which greatly enhances the horse. The inner leg should only act after the horse has “delivered the muzzle,” as it is called, to shift the hindquarters outward. This is a fundamental and distinctive feature of our bridlework, as all others tend to retain the hindquarters to harness greater power from the horse’s engine.

In the case of the opposite rein, the improper use of the inner leg aid also diagonalizes the aids, but in this instance, it holds no artistic value whatsoever.

When using the opposite rein along with the aid of the leg on the same side, the aids become lateral (ordinary school), which are more powerful but lack value in what is referred to as refined riding.

The value in our bridlework lies in the execution, where the reins are held evenly in one hand, approximately four fingers above the height of the saddle’s pommel, moving slightly forward at the moment of engaging them. However, they should never be held halfway up the neck or higher, as some riders tend to do—a habit that, when I have served as a judge, I have never rewarded, no matter how softly they handle the reins.

Regarding my statement that the reins are held evenly in one hand, this does not imply the existence of a bridle system with even reins, as some riders and enthusiasts have tried to assert. At the slightest inclination of the neck to one side, the reins can no longer be considered even. The rein becomes either loose, if managed, or opposite, since it is well understood that there is no effect without cause. Therefore, riders and enthusiasts must abandon the belief that their horses are bridled with even reins, as such a system simply does not exist.

“Note that due to the concentration of these technique aids, the left hind leg in support is under the mass, meaning at the center of gravity, and the right one is close (the driving motor), the upper back, and neck are the same, flexing or delivering to the chest’s tip, this being because the neck is not excessively bent, but the nape is flexed. As a result, the horse does not collapse, maintaining its vertical balance, thus allowing the rider to sit correctly, with the kidneys inward, using the displacement.

I said it is unique in the world because it forces the horse, in turns or movements, to completely deliver the nose or the leg of the rider, the stirrup, or the chest’s tip, depending on the progress of its education, and to throw the hip or croup outward. Both of these are foreign to all bridles or equitations. Although it is true that in high school riding, the horse is flexed (or bent while trotting or cantering), the execution is opposite; if the horse is walking in a circle, the head is pulled outward, and it is guided with the inner leg, and the flexion must be done by the nape, never by bending the neck, while retaining the croup, of course. Now, focusing on the bridles, there are three, used with one rein or opposite rein, as I will describe below.

FIRST.- The “On all fours,” which is when the horse performs all its movement while walking, marking its step without changing it even while rolling, before delivering, and upon delivering, maintaining the step while rolling is difficult because they always lack concentration due to the defective aids I have explained, and this causes almost all of them to “quarter”.

SECOND.- The “On the hand” is characterized by closing or delivering while fixing and turning on the inner hand (without defense for uneven terrain); and

THIRD.- The “Capeo,” which was used for our abandoned national tradition of bullfighting on horseback, which is on all fours, but without delivering to avoid losing time, very hollowed out, quickly releasing the croup to avoid being caught, all executed with great speed and momentum in both directions.

To clarify the use of the “one rein” and the “opposite rein,” I will say that the first acts by pulling the head toward the side of movement. To use it, the reins are taken in one hand, and with the free hand, the movement is requested or the horse is bent.

When the horse is quite soft and sensitive, it is handled with one hand, and in this case, the reins are held from top to bottom, with the fingers pointing inward and acting by the wrist’s movement. The opposite rein, which acts from outside to inside, that is, when turning to the left, is guided with the right hand, pressing against the neck. The reins should be held evenly, and the lower hand should move upward so there is no room for limping.

Any intervention with the one rein in an exhibition of the other hand disqualifies the exhibition, as does exhibiting the horse with the opposite rein.”

CHAPTER V

Aid

There are four aids: the sight, the hands, the movement, and the legs. With their proper use, accurate and orderly, a horse becomes softened and responds to the slightest indication, with the animal fully in the hands, legs, and at the mercy of the seat, so that the hands are not used roughly and only act as indicators and retainers of the vertical.

THE SIGHT – It indicates the attitude and posture of the head while observing discomfort, manifested by exaggerated closing and pinning of the ears when punished.

THE HANDS – Their softness provides the equestrian feel that is very easy in the Peruvian horse, as I have explained. From the front, their task is to seek and retain the vertical alignment of the head, hold back forward movement, and give freedom to prevent the horse from leaning, pulling, or striking when turning, depending on how the aids are applied (inside or outside). When stopping, they retain, and when relaxing, they pull.

THE MOVEMENT – The key to all good training, which unfortunately is no longer used by our chalanes, despite their forceful and harsh use when they attempt to “break in” or “saddle.”

As we see, movement is simply about placing the saddle. What initially was done roughly and forcefully must continue throughout the horse’s education and always when handling the horse. Over time, it should become smoother and almost invisible to spectators, though still perceptible to the horse, by simply retaining the inside leg, tilting the seat outward, and adjusting the outside leg as well.

Done correctly, this is the key in our bridle and all types of riding, with smoothness presiding and more force applied at the right moment when using the inside or outside rein. This reduces the action of the reins each day and prevents the habit of pulling and releasing the reins, especially when they boast of using the straps.

I say this is the key because it sensitizes and controls the moving or hinge part of the motor, which is the lower back. This point is perhaps the most deficient in the current bridle, where all effectiveness has disappeared in the violent movements demonstrated in the uncovered spiral and the “six,” which they cannot perform.

In the last horses I have ridden, bridled by different chalanes, only one stood out with notable sensitivity. In response to the movement aid, it yielded to the inside and, when placed and saddled, positioned its hind legs very deep, almost taking the huachano. Under the same movement, it sat and relaxed, noticing that its chalán only exhibited the inside rein. (The enthusiasts and chalanes will remember because I did this in front of the public.)

I also rode another horse, even awarded by me in bridle, which did not respond to the movement, even with all force and roughness, to the point that an enthusiast, noticing it, said: “You’ve encountered a cobblestone,” and indeed, it felt like riding a rock.

I must say that these horses, without an effective bridle, turn easily in both directions with almost extreme smoothness after the first signal, and continue spinning like a centrifuge, having their center of gravity in the back. If the deep mistake I’ve noted were not made, of touching or punishing with the inner stirrup, they would execute the rotation on their backs, describing a smaller circle with their front hooves and a larger one with the hind. They turn like a centrifuge because continuous work in this form intoxicates them, to the point that I’ve seen that to straighten their neck or turn them to the other side, the rider has to use their hands to push the neck.

This great lack of using the movement aid is evident in all movements. That is why, when walking in circles, rolling, or in figure eights, they appear straight from the hindquarters to the base of the neck, and only concave at the neck with the back sticking outward, instead of being concave in relation to the size of the circle they are describing from the hindquarters to the neck, flexing only at the poll, which is achieved only by touching or punishing with the outside leg to concentrate them.

THE LEGS – I have already referred to them when discussing the “motor horse” and “balance,” but I will expand on their use as an aid. They simultaneously push or direct the horse towards the rider’s hands, which should allow the movement to begin: when turning, in circles, and when yielding, the outside leg gives the command and the inside leg holds it. When sitting, if the legs touch the girth, they stop; if one or the other is alternately applied along with the movement, they make the horse back up (relax).

This aid is used with the proper pressure, using the stirrup, heel, or spur, depending on the sensitivity of the horse.

CHAPTER VI

Bits and Bridles

Another critical aspect often overlooked is using the same type of bit for all horses, even though most require different ones. For example:

A horse with a long neck, well-balanced in its natural posture, and a soft mouth should be bridled high with a thick, arched bit and relatively short shanks.

If such a horse is fitted with a low-placed bit, a thin arch, and long shanks, it will overbend, meaning it will tuck behind the vertical, posing several risks, such as stumbling or tripping, locking up, and, if ridden with opposite rein pressure, it will keep falling and rolling without yielding, as its muzzle remains stuck against the center of its chest.

I once rode one of these horses that had been properly bridled, but it still rolled on every surface. It had developed the bad habit of chewing the bit with both jaws in that position.

Another horse with a short neck, with or without a pronounced crest, should be fitted with the bit in the harmful position described for the previous horse, as its flaws are the exact opposite.

Then there are others with low withers and an inverted neck that tend to carry their heads too high. These should be bridled very low, almost touching the canine teeth, with the curb chain relatively loose. Of course, such horses, whose flaws cannot be corrected with the knowledge of our traditional bridling techniques, should be trained for practical work rather than for show bridling.

In short, to bridle correctly, one must carefully assess the horse’s neck and wither structure.

CHAPTER VII

Age to Saddle

Some may find this booklet lacking because it doesn’t cover anatomy, diseases, or treatments. However, with so many professional works available on those topics, it would only leave me with copying them.

Similarly, I won’t delve into the detailed process of taming, such as how to fit the halter, blinders, saddle blankets, saddle, etc. However, I will emphasize that a horse should be fully tamed by the time it reaches the age to be saddled. In other words, it should already be accustomed to the saddle, girth, and crupper, and have been worked on a lunge line.

An enthusiast’s pride should be to ensure that the horse doesn’t make a single buck during its first saddling. The appropriate age depends on how the horse has been raised, particularly its diet. Under the common practice of watery pasture feeding, horses are often underdeveloped. Their growth is slow, their bones lack strength, and their muscles remain underdeveloped, among other issues. In many cases, they are raised so poorly that they live in a state of anemia, which, despite being fed grains later on, often becomes almost a chronic condition.

By three and a half years, a well-fed and exercised horse may have nearly reached its full height, making this the ideal age to begin training. At this age, horses tend to be more flexible and docile. In contrast, older horses often develop undesirable traits, either naturally or due to harsh handling.

Early training also promotes balance, as neglecting this can lead to a horse becoming front- or rear-heavy. Correcting these imbalances later on is an unpleasant task.

By fostering proper balance, the horse’s form becomes more harmonious, as it is undeniable that a knowledgeable rider is like a sculptor, shaping the horse’s physique.

CHAPTER VIII

Bridling or Training

Before outlining the rules, I must emphasize that to truly understand and experience the artistic pleasure of riding, one must first grasp the principles that govern the “motor horse”—the laws of balance for both the horse and the rider, and how these laws function together. Whether dealing with a native horse or a trotter, these principles remain essential.

The distinguished bearing of the animal, the rhythmic and measured movement of its reactions, create an artistic equilibrium that unites rider and horse into a single harmonious, proportionate, and elegant entity. In this unity, the trained horse and skilled rider achieve the highest artistic effect with minimal physical effort—avoiding any abrupt, harmful, unsightly, or dangerous movements.

Diameter of 12 Meters (Training Ring)

(Lamina N 7)

The horse must be worked in both directions, ensuring it neither drifts outward (rolls out) nor cuts inward (steals the circle). Only in the designated areas should it be turned. The future of a young horse greatly depends on the knowledge and skill of the chalán (trainer), who must know how to maximize the unique advantages of the Peruvian horse.

From the very first dling sessions, the horse’s natural gait—the one it can perform most easily and elegantly—should be prioritized. The goal is to avoid artificial movements and cultivate the horse’s natural ability. In the early stages of training, more attention should be given to the horse’s comfort and confidence in executing the movement than to its precision. It’s unreasonable to demand something from a horse that it hasn’t yet developed.

Many people mistakenly believe that when they see a horse moving with arrogance and grace, it’s solely the horse’s natural talent. They fail to acknowledge the trainer’s role. This is a significant error. While it is true that the horse’s natural ability is crucial, the quality and harmony of its gait are the result of the trainer’s education.

The lack of recognition and encouragement for chalanes is a persistent issue. Although many lack formal technical training, some have an innate vocation for riding and an exceptional equestrian touch. These trainers guide their horses with impressive poise. When the public praises a well-trained horse, the owner, if present, proudly responds, “It’s from my bloodline,” a charming expression reflecting the pride of owning such an animal. Pride, as always, blinds us, and in this case, it conveniently transforms the horse into a “relative by blood.”

This lack of acknowledgment for the chalán is mirrored by the general public’s attitude. I often wonder why, when it comes to the relationship between a person and a trained animal, we tend to value the animal more. For example, when a horse passes by with a magnificent gait, a proud posture, and the balance I described, people exclaim, “What a fine horse!” If it performs well under the bridle, they say, “What a skilled animal!” But the rider? Nothing. Despite the fact that the horse is beneath, and the man is above.

Once the horses are well “broken” and confidently walking in the larger circle of the training ring, they are then guided through smaller circless (Lamina N 8). These smaller circles coincide with the points where they were previously turned in the larger ring, and the horse must complete these circles in both directions.

Now, I will move on to the specific rules or aids that should be employed in their training. This process always begins with the halter and continues, as an intermediate stage in their education, with the use of what is commonly known as the four reins. I will not delve deeply into explaining or proposing fundamental changes to the somewhat illogical use of the halter, so I will proceed directly to describing the steps:

1. “Walking”

When taking the horse out to walk, it should be done in a straight line, accompanied at a short distance by another horse to serve as a companion or “nanny” (amadrinar).

2. “Turning”

Once the horse is walking somewhat steadily, it should be stopped in a narrow space and gently pulled to the right or left rein without abruptness, applying more pressure with the opposite leg.

The rein pull should not be a single, continuous movement. Instead, the hand should yield slightly with each response the horse gives, aiming to bring its muzzle behind the rider’s calf. This exercise should be repeated in multiple sessions until the horse responds to the slightest cue in both directions. During this initial phase, all training should be conducted in a straight line before transitioning to the training ring.

As the halter work progresses and the horse begins to learn various movements, the rein pull, which initially positions the horse’s head behind the calf, should gradually move toward the stirrup, and from there, to the center of the chest. This progression encourages the horse to collect itself more effectively.

I mention this progression because it is traditionally followed. However, in my opinion, teaching something incorrectly only to later correct it is a waste of time. If positioning the head behind the calf is considered incorrect, and positioning it at the stirrup or, better yet, at the center of the chest is correct, then that is how the training should begin from the outset, (Lamina N 9).

Since flexion or bending is already performed at a high level and in the indicated good positions, if one wants to rein them in opposite directions, after the so-called direct rein has been applied, it must be accompanied laterally by the opposing rein.

Due to the anterior limb’s displacement when using the continuous direct rein, it is advisable to alternate between reins to correct the defects of each rein technique. However, during an exhibition of a trained horse, the rein should be used either solely as a direct rein or solely as an opposing rein, and not, as commonly seen, switching between both until the horse bends and then pushing with the opposing rein, which diminishes the exhibition’s elegance by using both hands, as I have previously mentioned.

3.- “Torno” (Walking in a Circle)

Once the horse walks directly and confidently and is properly bent, work begins on a large circular area (ten to fifteen meters in diameter), ensuring from the start that the second and subsequent laps follow the tracks of the first one, not allowing the horse to drift outward with the outer leg or to cut inward with the inner leg. In this way, the horse’s tracks should describe a perfect circle, (Lamina N 10).

“8” (This and all diagrams are drawn with precision, but that doesn’t mean the movement should be executed with such perfection). Two laps are first completed in the circle, and then the figure-eight begins, changing hands and subsequently direction at the markers C and D. In both large and small circles, care must be taken not to drift outward or inward.

Once they walk freely, they should be bent (or flexed) within the circle (Lamina N 7), continuing to circle while always bending from the outside to the inside. If turning right, use the right rein and left leg, and vice versa.

Once the horse achieves the desired flexion in specific areas, they will then be directed to perform smaller circles

(Lamina N 8). This is done alternating between both hands, ensuring that in smaller circles, flexion is asked for and then released simultaneously, without holding or constraining them, ensuring the horse continues to move fluidly, marking all four legs.

Regarding the rider’s seat position during the circle, if turning right, the seat should shift slightly to the left as needed to align the horse’s body with the circle, with the left leg slightly behind the girth and the right leg firmly at the girth. For left turns, the aids are reversed. The left leg placed back will prevent the horse from drifting outward, while applying corrective pressure will keep them centered, (Lamina N 11).

Double “8” – The purpose is to soften the horse and prepare them for the “Caracol” (Spiral), executing it with the aids described.

4.- “Ocho”

This consists of drawing two connected circles, changing direction precisely at the point of connection, alternating hands. Although it is simply drawing two circles, when executed correctly with the specified aids, it is essential in Peruvian rein control. Performing it without adjusting the rider’s balance or seat during the hand change will yield poor results. Properly executed, it becomes crucial since it is the only movement, aside from sitting and backing, that contributes significantly to balance.

Overusing the figure-eight undoubtedly softens the horse but can lead to what is known as “emborrachada” (a loss of focus and sharpness). I have prepared several diagrams for its execution (Láminas 9, 10, 11).

As with all training, start with larger circles, which serve as a basis for evaluating the horse’s posture: even strides, smooth movement, well-collected front limbs, high neck, correctly positioned head, vertical forehead line, contracted loins, collected body, loose reins without relying on the bit, and proper balance. The horse should walk freely, ready to respond without drifting outward or inward. This is where the trained horse’s quality is judged, (Lamina N 12).

Before performing the spiral, complete two laps around the larger circle, gradually reducing the diameter, paying attention to posture and footing, and aiming to bring the horse as close to the center as possible, then exit the spiral in the same smooth manner.

When riding at high speed (a caballo destapado), the execution remains the same, except the entry is faster, maintaining precision without stumbling.

Throughout the movement, enter through the right, as previously indicated, and exit correspondingly, changing directions at points C and D. In smaller circles, properly executed figure-eights require aid transitions at the connecting space between C and D, alternating hands like in all figures.

The purpose of the caracol is to shift and mobilize the hindquarters. It is performed using the same aids as for circling, progressively tightening the circle until reaching the center, where flexion is induced with either the direct or opposing rein. Once the horse is focused, allow it to roll on its footing, closing the circle.

Only at this point should the inner leg apply a stirrup or spur tap to push the hindquarters outward. When done correctly, the horse should enter and exit on the same path and footing.

The “snail” is also executed in the “8” (Lámina 13)

6.- “Rastrillar” (Sliding Movement)

This involves engaging one or the other hind limb while descending a ramp, such as the slope of a bridge. If turning right, pull the right rein after making contact, shift your body in that direction, adjusting the seat and kidneys, and then release. For the left, apply the respective aids. This prepares the horse for the “sitting” and backing movements.

7.- “Sentar” (Stopping)

This is similar to the previous exercise but involves bringing both hind limbs under the body using the same aids as in rastrillar, firmly adjusting the legs to the girth before engaging the reins.

The remainder of the document provides similar in-depth techniques for training and showcasing Peruvian horses with precise aids, rein use, and corrections. If you’d like the entire document translated, let me know, and I’ll continue.

The “6”

Whose execution rules have already been given, and must be performed after having led the horse around the circle twice, executing it to the left and right.

8.- “Cejar” (Stepping Back)

Once the horse knows how to drag its feet, it is taught to take a step back after stopping with the aids used for dragging, always yielding the hands. In other words, the hands should not pull or tug continuously but only when the saddle shifts.

Although it is a backward movement, when well-executed, it should be diagonalized. This is where the importance of displacement comes into play.

When the horse steps back by moving the leg and foreleg of the same side simultaneously (laterally), it diminishes the horse’s stature and limits its mobility or quickness, as there is no concentration.

WORKING WITH AN UNRESTRAINED HORSE

When everything mentioned above is performed calmly and with collectedness, responding to the slightest indication, the horse is ready for this phase, which is the ultimate test of the bridlework’s completion. It demonstrates that the horse is trustworthy and secure.

The first movement is a “spiral,” making two turns around the large circle on the ground, then commanding it to gallop freely, reaching full speed. Once this is done in both directions, closing in the center, the “8” is performed in the same manner, albeit at a slower speed due to the smaller circles.

The speed in both the start and the closing, along with a good posture without breaking form, reflects proper bridlework. This depends on the horse’s spirit and agility.

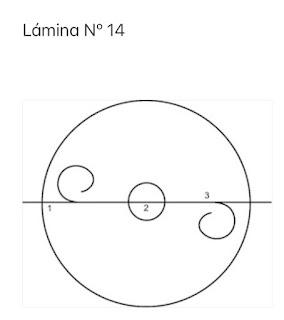

A challenging but necessary test is the “6” (Lamina N 14).

After completing two turns around the circle on the ground, enter at point 1. At point 2, the horse is seated and steps back to point 1. From there, it is commanded to accelerate to full speed toward point 3, where it is stopped and handed over. Performing this on both sides demonstrates complete control over the horse, where displacement is most essential.

AVOIDING GROUND STIFFNESS

Overusing the previous exercises may result in the horse becoming stiff on the ground. This can be corrected using the following aids: When leading the horse to walk, shift your seat from side to side, accompanied by light taps on the horse’s flanks with the stirrups. (On this note, it is worth mentioning that some riders execute this slightly behind the girth, producing a loud sound, especially when the horse is sweaty; this is known as “planeteando”).

By yielding the hand, repeat the process. If a descent, however slight, is available, it can be beneficial.

Ultimately, success is achieved through an intelligent combination of aids, such as hands, displacement, and legs, which are described later in this manual.

To someone inexperienced in equitation, it may be difficult to understand the details of these aids and appreciate the harmony between them and the horse’s actions. Aids are involved in every movement or action of the horse and are only absent when the horse is not being ridden. Although we have said that training takes one year, it only stops when the horse is without a rider. Hence, well-trained horses often lose their bridlework and responsiveness when handled by inexperienced riders.

SPURS

I almost forgot to mention spurs. They should be introduced almost simultaneously with the bit, gradually accustoming the horse to them. The initial touches should be very gentle and not repeated frequently to avoid the risk of the horse swerving.

When used as a form of punishment, spurs should be applied forcefully and toward the rear, producing decorative scratches. It is important to remember the old saying: “The better the horse, the better the spurs.”

Note:

The use of four reins, meaning both halter and bit, should begin when the halter training is advanced, and the horse works well on the lunge, bends, and stops without sitting or dragging its feet. This work should start with the four reins, initially without the horse feeling the bit.

At the beginning, the bit reins should be loose to prevent the horse from becoming timid due to the sensitivity of the so-called “bars.” Gradually, as the horse works on “8s” and “spirals,” the bit reins should be used more frequently, eventually leaving the halter as a corrective tool only.

The halter will later be replaced by a cavesson, which connects with the mouth and serves as a reminder of the correction. Regarding the “bars,” they refer to the space between the molars and canines of the lower jaw. Their sensitivity determines whether we consider a horse spirited or sluggish in the mouth.

ABRIDGED TRAINING FOR EXHIBITION

When a horse needs to be quickly trained for an exhibition, the day before or the day before that, the “bars” can be broken to induce bleeding. This is done by using the bit bridge or replacing it with a leather strap. The rider must feel the contact and determine through touch when they are on the “bars,” then apply a quick, forceful pull.

This should never be done with loose reins, as it would have harmful effects, producing the dreaded “bitting,” which causes the horse to lose its vertical posture.

When training with opposite reins, their use should be introduced progressively as soon as the bit is employed. Initially, this is done without using the direct rein, followed by displacement, and gradually, until the horse responds to the opposite rein. Over time, the use of the direct rein should become less necessary, eventually employing it only for slight, quick adjustments.

As explained, daily work should alternate between the direct and opposite reins to prevent excessive displacement of the horse’s shoulders.

JUDGING

Judges’ evaluations and scores regarding conformation should consider the characteristics described in Chapter II. In my opinion, if there are no significant defects, this score should be lower than that for floor quality, softness, and elegance, as these are the true distinguishing features.

Regarding bridlework, the established rules should be followed, requiring work with a single hand when using the opposite rein, holding the reins evenly, with the hand facing upward, and when using the direct rein, the hand facing downward.

Size should be given significant importance.

All falls and abrupt movements mentioned earlier, as well as stopping without command, opening the mouth when seated, stepping back without moving diagonally, or retracting the head completely behind the vertical (overflexing), are considered faults.

Lima, July 1945

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario